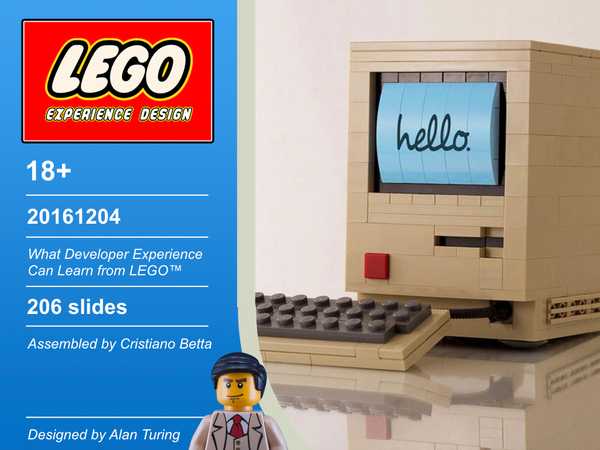

Developer Experience lessons from LEGODecember 14th, 2016Cristiano Betta14 minute read

Have you ever thought about how much first impressions matter?

We all know the cliche anecdotes about how first impressions matter in dating, but that’s not what I want to talk about today. Today I want to talk about the first impression that your product makes.

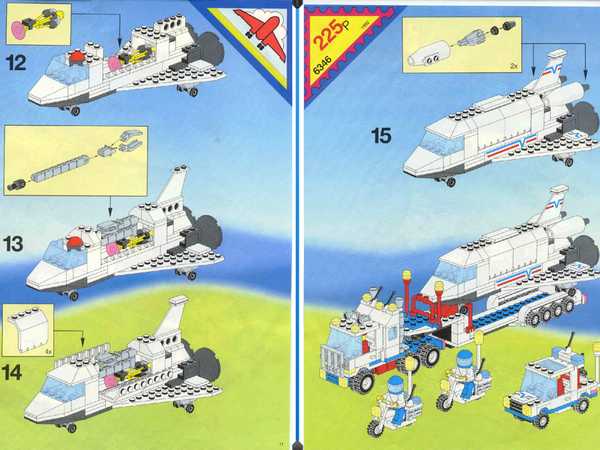

This is my Space Shuttle from LEGO box 6346, produced in 1992.

If you weren't fortunate enough to have been bombarded with LEGO as a child as I was, I assume you probably still know what LEGO is.

It’s the brick building toy for children that has many middle aged people reliving their childhood. It’s the toy that has us connect 2 bricks, and then another few, until eventually you have come to building a complex structure with close to little understanding of architecture or mechanical design.

It was invented in the 30's and it’s gone through many iterations, and like IKEA’s Alan key there’s a few things that have remained core to their product.

My name is Cristiano Betta, I run a small consultancy and focus on Developer Experience.

One of the things I like to do is to look at the onboarding and get started experiences of companies like Stripe and Twilio and write up what’s exceptionally good or bad about them.

Today I am going to take a similar look at what we as product owners and evangelists can learn from LEGO’s onboarding experience. Along the road we will learn a bit about human psychology, first impressions, and how all of these can affect your product and your developers.

The LEGO experience really starts with the box. It’s a very familiar design.

The big red logo, the characters, the product number, the indication of complexity. But there’s so much here that isn’t quite that obvious: LEGO has done a lot of work to put us at ease with this design.

It’s often easy to forget your external developers are not the awesome Master Builders that you are (yes that’s a LEGO term). They haven’t experienced your product before, they probably haven’t even experienced your industry before. They don’t know what your product does and probably don’t know what it’s for. And not unlike the average age of a first-time LEGO builder it’s not unlikely that your first time users are a LOT younger than you. And with young age comes a lot less technical experience, or even life experience, though probably a relatively high ratio of LEGO experience.

LEGOs job with the design of their boxes - besides selling you the product - is to overcome those deficiencies. The boxes are there to inspire you that you will be able to do amazing things with their product. They show you the finished product, the parts it’s made off, and sometimes even some of the basic assembly steps. The more complex products also show the variations you can make with it. This is core to the LEGO experience, but if you think about it it’s also core to your product. You don’t just want people to implement the samples you’ve made for them, you want them to build your product into their product, potentially even in ways you had not thought about yet.

The real thing a first impression is about is not to look good, or to have the best product. Rather it’s about making sure people have the confidence that they will be fine. We want to motivate them and inspire them. We also want to make sure they know that they are going to be able to do this, even if they’ve never used your product before and are very new to programming.

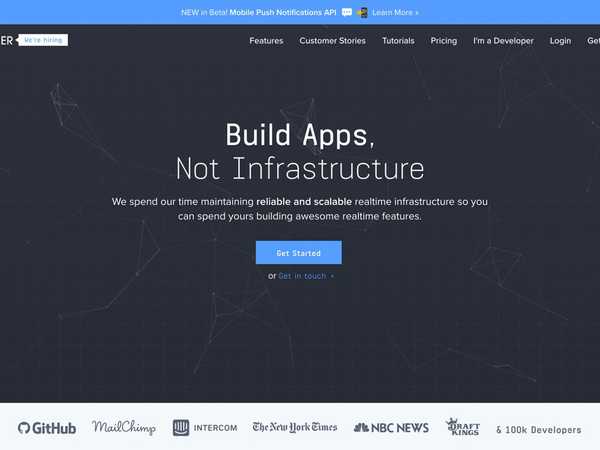

In technical products there are a few ways we can approach this. Firstly we need to motivate and inspire developers. We need to tell them that our products are going to solve a problem they might not have known they had. I personally love the demo that Pusher has on their site.

In a few seconds, and without mentioning how it’s done, they show you how easy it is to push an event to any browser. With one cURL command they instantly get a developer’s mind going and thinking “oh, interesting, this would make XYZ a lot easier”. And they did all of that without boring you with the technical details.

Which brings me to my second point: it’s important to give your developers the confidence that they (and not just you) can do this. As a product owner we need to make sure we make them feel smart even if they have almost no development experience.

Pusher does a great job of this by keeping the jargon low. They don't talk about web sockets, they keep technical terms and acronyms low. My only remark would be that the this demo still requires people to be familiar with cURL. That one step of being able to copy paste something in a terminal is a point of failure where people might not know how to do this, causing a potential drop off.

In general I find that images, videos, gifs, and other interactive click-demos tend to be less error prone.

Once you have reached these 2 goals of inspiring and motivating you have done something extremely import: you have given your developers the confidence that they are ready to Get Started.

And LEGO is great at getting people started.

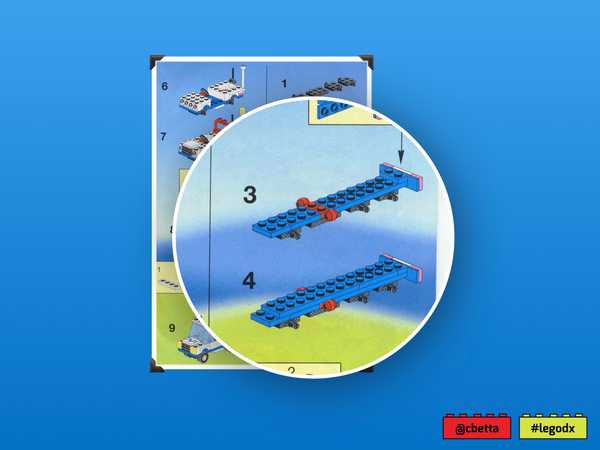

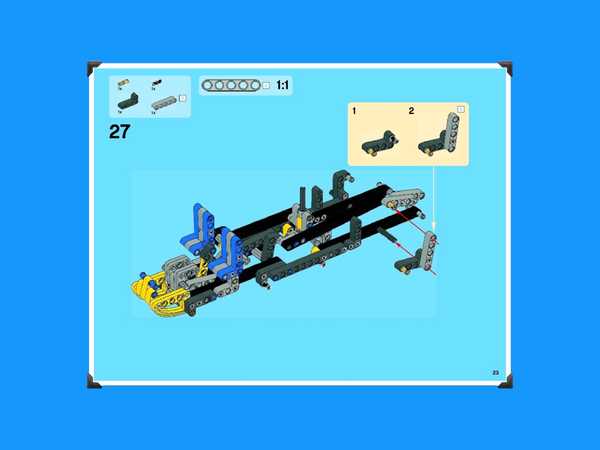

A LEGO instruction manual is the ultimate Get Started guide. It’s included in almost every box and it helps people to go from zero all the way to hero, helping them in every step along the way. It’s an amazing achievement that all of this is done on paper, without any text and without providing any technical explanation as to what’s happening.

See, the human learning process is a feedback loop that promotes small steps. We learn, reflect, and repeat.

Between reflection and repetition we adjust our mental model of what we are doing before we try again. When we reflect and find a large discrepancy between what we expected and the result it becomes really hard for us to adjust. LEGO has mastered this process in their manuals.

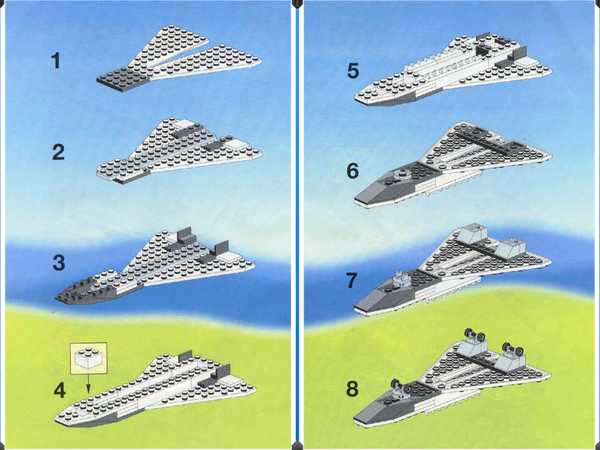

As you can see every manual really just starts with a few bricks. And then a few bricks more.

If you’ve assembled a few LEGO boxes like I have, you’ll start to notice a few patterns. For example, there’s a few ways to ensure that your creation is structurally sound. By interlocking your lego blocks you can make stronger walls. What’s great is that this is a common practice used in architecture, and aerospace engineering, but it’s not labeled or named within the LEGO manual. Instead, people are simply shown, step by step, how to do things the right way.

LEGO does this without resorting to jargon, and therefore without creating an artificial divide between the professionals and the amateurs.

I want to take a little sidestep here.

It’s important to remember that your product is not an Apple product. Apple has mastered the design of products that do not need manuals. And in all honestly, I love that.

It’s great when products are intuitive and easy to use, when they are forgiving, and self correcting. These products don’t need manuals, but again: your product is not an Apple product.

The expectations of your product are vastly different than that of Apple. Inherently any developer focussed product, whether it’s an API or an SDK is going to require more specific input, input that’s less forgiving, less self correcting. And in exchange your product is also going to be highly efficient in solving certain problems, problems developer might not understand yet when they start using your API.

So just like LEGO’s interlocking bricks will teach people how to make a sound structure, your manual will need teach people how to do things they didn’t even know existed.

I want to reiterate how important it is that these manuals take someone all the way from zero to hero. From brick number 1, to a full space shuttle.

If LEGO would only take you halfway there and then left you on your own to make a real product, the satisfaction would be immensely lower. Yet many of the sites I’ve looked at that have a Get Started button rarely take a developer all the way there. Often they take someone from 0 to signup, but then leave the actual implementation as an exercise.

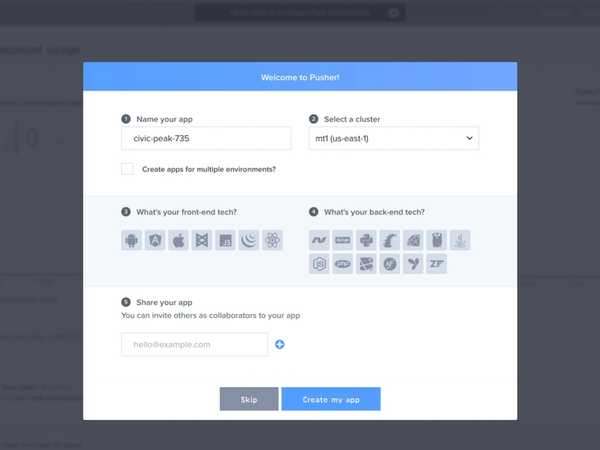

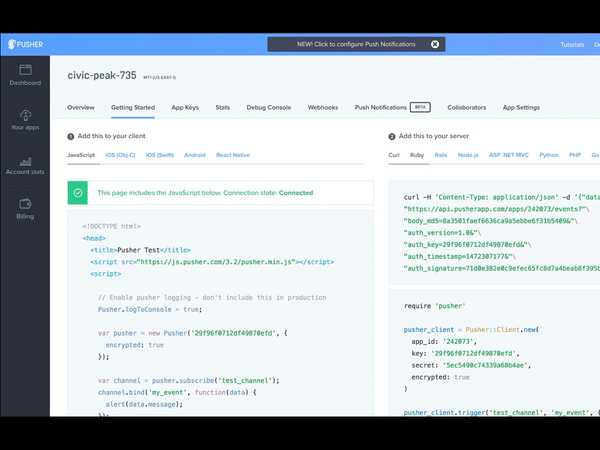

Again I’d like to highlight what a great job Pusher has done in this aspect.

They take you from Get Started...

to collecting your first building blocks…

to providing you with step by step instructions.

Which brings me to the important fact that every step matters. Every brick, every 10 seconds are important. If your Get Started guide gets someone through the steps we mentioned before, and manages to inspire, motivate, and signup up a developer, then your next steps should, and must be, to help them to start making those first API calls. To build that first product. To finish their Space Shuttle.

Let’s look at something else.

Have you ever looked at how people find the next LEGO piece they need? Or for that matter, the next screw in their IKEA set? Or the next puzzle piece?

People do not evaluate every piece on the table, this would be insane. Instead they try the first piece they think is relevant and give it a try. When they discover the piece was not what they expected, they trackback to the last known correct configuration and try again.

This behavior is called satisficing, and it’s the same behavior we see in people who make fast high stakes decisions, like fire fighters. It doesn’t make sense for them to evaluate every option and make a grand plan, as in the meanwhile there's still a fire going on. Instead, they rather just get going and adjust along the way.

In an API or SDK this can be accounted for by adding some level of self correction, or forgiveness to the product. One way to do this is to add detailed error messaging that signals to the developer what mistake they made.

Now, it would be tempting to provide a big note in your guide, like LEGO does when 2 pieces are very similar, to prevent developers from making common mistakes. But as a product owner I’d almost always recommend to instead improve your API or SDK to be less ambiguous, to remove the confusing elements rather than patching them with bits of text that nobody reads.

Which brings me to the following. If you take one thing away from the LEGO manual it’s this: nobody reads text.

The average website visitor takes less time than it takes for you to blink to determine what your site does, what it’s about, what specific page they are on, and what they can click on.

As much as you might be some artisanal crafter of excellent technical copy, in the end, people not going to read your copy. Instead they are just going to try and build what they think they can use your product for.

It’s also easy to think that your product has some specific purpose, that you thought of first, and that this is the only thing people ever want to use your product for.

The reality is very different though. Just as every LEGO brick has a million different use case, your product will, and should be able to be used by people with crazy ideas you never imagined.

Take this door for example. It’s probably one of the most specific bricks out there. It’s a door. Yet I’ve seen it used as a wing of a small plane, as ears of a bunny, as a speed bump, and much more.

The LEGO building experience doesn’t end with the set you bought. For example, this Space Shuttle has actually spent about 18 years or more in separate pieces in a box because when I was 16 I decided I’d build something new out of it. I never got around to reassembling this until a few weeks ago. Not kidding.

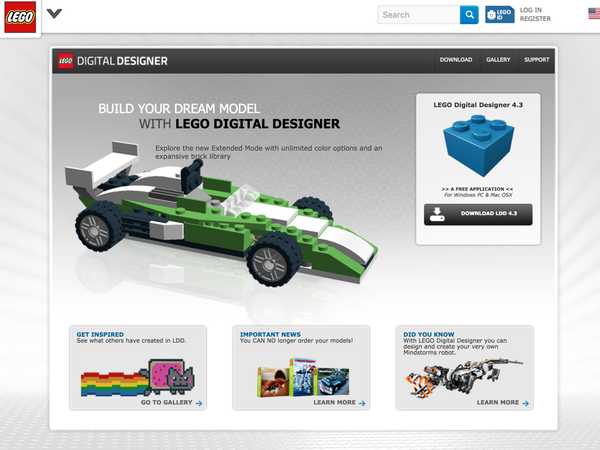

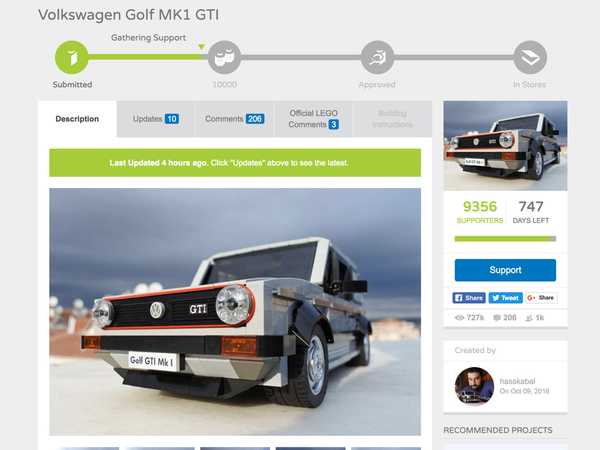

LEGO has fully embraced this tinkering. They have something called the LEGO.com Digital Designer Virtual Building Software, which you can use to make new creations, and share them on ideas.lego.com.

And when you make something, and it receives 10,000+ upvotes, then LEGO will consider it as an official box, and release it.

And you’ll be mentioned as the creator, making you a Master Builder!

Yet when it comes to developer products we often stop supporting people after their first implementation.

I recently build an Alexa Service for the Amazon Echo. Amazon, besides having a pretty horrific Getting Started experience, has a pretty horrible experience for submitting skills as well. It took me 3 attempts to get my skill submitted even though I had to fill in 4 or 5 forms of virtual paperwork. In the end, when my skill did get accepted, there was no congratulations and no celebration of my submission.

And it’s important to celebrate the success of your external developers!

The support for developers should not end at that first implementation, rather it should continue all the way into every product they build, every project they use your product in, and every crazy variations that they might consider.

The developer experience should not be of Learn -> Build -> Reject...

... but that of Learn -> Build -> Share.

To summarise I think there's a few core lessons we can learn from LEGO.

The first is the idea that we all learn differently. That we all have different starting points when we start building something new. We all have different experiences and motivations. We all have different needs to be motivated or explained.

And when developers start building on your platform, every 10 seconds matter. Even the first 10. As the first 10 influence the next, and the next and the next.

If you drop a user at any point, if you don’t allow them to succeed, if you’re not flexible to failure, if your product doesn’t self correct, the next 10 seconds will be with your competitor.

So when a developer finally succeeds on your platform, make sure you remember all the hurdles they overcame. All the learning they did about you, your platform, your industry, about everything they did not think they ever needed to know.

When you’ve spent this immense effort to inspire and motivate developers to even give you a chance in the first place, and they then build something you couldn’t have imagined, then celebrate their success as yours!

Making it easy for your users to succeed makes it easier for you to succeed.

I leave you with this.

_You can write the best copy in the world, and have the best instruction videos ever made, and the best developed product ever invented..._

_...but when someone steps on a LEGO brick it still hurts._

Thank you.